INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ROMAN CANDLE ISSUE 1 – AVAILABLE HERE AND HERE.

No one ever admits it, but a lot of ‘photobooks’ are pretty dull. £40 for page-after-page of po-faced portraits? What a swizz. And how about those supposedly intellectual photos which just show the corner of a hedge or something… school textbooks were more fun.

One photobook which most certainly IS NOT DULL is a seldom-spoken-of gem called Vagabond by a chap from Tulsa named Gaylord Herron. Released back in 1975, this is a bizarre ride way beyond the far side, showing such amazing sights as a pair of overweight wrestlers, a proud man’s hat collection and a teacher sat by the roadside scoffing a slice of cake.

There’s paintings too. And words about Cain and Abel and Tulsa and trips to Japan and countless other things. The whole thing is a thick and hearty soup worthy of wading through, and repeat servings are advised.

Gaylord, or G.Oscar, as he’s sometimes known, now runs a bike shop which sells affordable vintage bikes. I called up the shop phone one morning to pester him about Vagabond and anything else I could think of…

I can’t say I know too much about your home city of Tulsa. What’s it like there?

Tulsa is kind of becoming more of a cosmopolitan city than before. There’s a family foundation called Kaiser, which covers the whole country, and they built a park here, which is the most incredible thing in the world. It’s a huge, huge park, which has won the award for the most outstanding park, worldwide. He hired people from Holland to design a lot of it.

Sounds nice. How big is Tulsa? What’s the population?

With the surrounding towns around it, it’d be a million I guess. It’s not that big.

What was it like growing up there? Was it the typical America you’d imagine from films and books in the 50s?

Well, it was more of that rural kind of feel. It was an oil town—it grew out of oil. I think it became an incorporated city in 1907, so it’s only just over a hundred years old. It was built on the curve of the Arkansas River at a place where Washington Irvine and those guys used to hang out. It’s a really historic area.

So that’s kind of the hook—the river—which has been developed and exploited in all kinds of ways over the years. But now it’s kind of taking on the feel of a larger city.

When I was a kid, we grew up near downtown, and we’d ride the bus into town, because we just didn’t have the money for all kinds of things that other people had. And I remember seeing the skyline in the distance on the bus, and thinking how neatly it was done—it was good math—perfect. Of course, that skyline has been decimated since then, it doesn’t have the architectural look or the charm that it once had.

But at the same time, there’s an area in midtown that’s about nine square miles of old growth trees that are there because of the watershed coming down from that curve in the river and making it very, very fertile. You British would call it a wood.

Yeah, or maybe a ‘copse’, although not many people use that word.

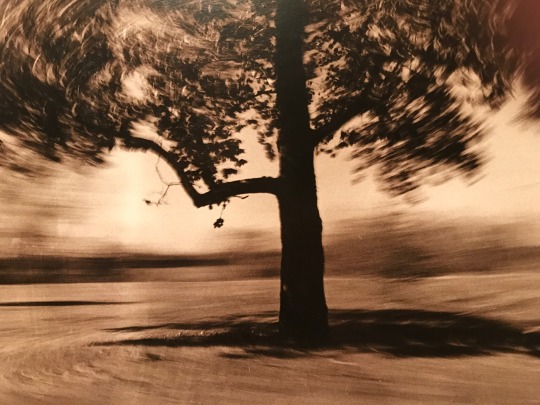

There’s a lot of European paintings of that kind of thing. They haven’t decimated it with pharmacies and parking lots, although I’m sure they’d love to. I’m taking photographs of the trees to call attention to it—I wanted to make people aware of what they have in Tulsa.

Do you think people take that kind of thing for granted a bit?

Yeah, they do. There’s this dappled light at the base of these trees, which filters down through the canopy and splashes across the ground, and that has a psychological draw for people. They get into that dappled light, and they don’t really realise it’s doing something to them, making them relaxed, making them feel protected—it’s neat. But when I first started taking pictures, I used to avoid dappled light. I didn’t want it, it was too chaotic and confusing. I liked solid blocks and shapes that were well defined. But at my age now, I love that dappled light—I look for it.

From what I gather, you started taking photos when you joined the army and went to Korea, but had you any interest in it at all before then?

Not a bit—I really hadn’t. I mean my sister and I would do goofy shots out in the front with a Hawkeye camera when I was a kid, but I didn’t do anything until I got to Korea.

You see what happens is you go in there and they say, “Let’s go to the village.” And they’ve all got cameras around their necks. So by about the third or fourth trip, I went and bought a camera. I remember it was a Petri, and then after that I got a Honeywell Pentax PX.

So I’d go out, and shoot these slides—but then one day I decided to try black and white—and one of the better pictures I’ve done was on that roll, at the very beginning. It was shot out of the bus window, going down the street. I shot these guys who were out on the street, these old timers who had been in the war and were reminiscing. It was just a neat shot.

And at some point someone said, “You know you can make a print off that?” So I went into the darkroom, and I get this picture. It’s a guy on a cart eating an apple. He’s a human truck, waiting for his next job. So I print this picture of him, and it was still wet, but I ran down to the club where my buddies were all drinking, and threw this print down on the table. And they went, “Ooh, look at that! That’s great!” They were all over it, and that was all needed. So I ran back to the darkroom and I was there ever since.

You just thought, ‘right—this is what I want to do’?

Yeah. Then I started messing around with cropping and all those other elements of art. I started really examining everything, until I got to the point where I was just excessive.

What sorts of things were you looking for back then? What were you trying to show?

Chronologically, it starts with me taking pictures of people farming along the Han River. Those kinds of things that were related to a kind of rural mind-set. But then I just expanded into all other kinds of things. What I realised then is that with a twist of this, or a twist of that, you could make a whole new world out of these images. I saw the potential for all the kinds of things you could do to change the feel of a print.

And now, later on, I’ve came to the conclusion that what I was looking for was perfect math. Everything is math—the frequencies in colour, lengths and distances, ratio and proportion—and if you frame it, and put it in a rectangle, then you’ve got the potential for perfect math. Or maybe something that’s perfect on one side, but not the other side. And all those kinds of unknowns.

The eye picks it up, sees it, then the mind says, “What’ve we got here, let’s put a rectangle on it—it’s perfect.” And then you shoot! Bang! Hit the shutter! And that’s what it is, isn’t it?

Your photographs aren’t maybe what I’d think of as being ‘mathematical’— they’re not straight, stiff architectural shots—they’re loose, and some parts are blurred, but I suppose maybe they’re mathematical in the real sense… rather than someone just lining their camera up 90 degrees to a subject.

Yeah, and I’m dealing with this now in another sense. My wife died about five or six months ago, and I’m still in that in-between land. We were married 50 years, and she was part of this bike shop with me for 22 years. And when she left, I started doing something really odd. I had some craft paper on a roll, and I brought it over to my bar. I taped it down, and I started darkening these frames which I wanted to put around these old sepia tone prints.

I wanted it to be this really, dark, dark brown. Almost black—but if you look at it next to a colour it’ll pick it up and amplify it—it really incentivises the silver to pop out at you. And it’s working a charm by the way.

So I’m doing this, and I splash some ink—well actually, it’s more of a stain like what you use on furniture. And on this craft paper I’m doing this very physical, violent Jackson Pollock kind of thing, and all of a sudden, these faces are coming up out of this paper. And I’m getting pictures of my wife, pictures of my kids and pictures of people I know, coming up out of this craft paper. And you talk about loose, this is as loose as I’ve ever been.

It’s that thing of the mind joining up the gaps?

You’re looking for math, your brain is looking at what you eyes are sending in, and it says, “Wait a minute, I recognise this.” But you didn’t do it on purpose.

And another thing when you talk about mathematics… I shoot a lot of photographs at a 15th of a second—even in the bible it says that’s the twinkling of an eye. So I shoot these drive-by photographs at 40 miles and hour and I realised in looking in these pictures that a lot of stuff comes and goes in that 15th of a second that we won’t see with our eyes. It real mysterious. It’s like a no man’s land of time— a warp of time.

I suppose if the eye processes 25 frames a second or whatever it is, what’s going on in the in-between time? There’s could be all sorts of stuff.

Yeah, that’s the point… there’s stuff in there. And I’m getting to the point now where I’m seeing faces everywhere, in all kind of objects. And I’m loving it. I’ll say that if you want to get over loss, and get through the pain, use art to do it. Make that your vehicle—and use your hands!

Art is a thing that is so hard to define, but I’m starting to think that it’s picking up impulses from the past, and fitting them into your current situation. And that’s why art doesn’t have to be anything in particular, there just has to be a connection. That’s what it has to be.

When you were in Korea in the early 60s, were you thinking of making art?

No, I can remember after a couple of weeks of doing those prints, I had a photo of some laundry hanging on some clothes-lines in a house in Seoul in the snow, and I made a print of this, and I turned it on its side 90 degrees, and all of a sudden it’s like an exotic seascape. It was all being done with this white linen laundry. And I thought this was unbelievable. You could twist it, turn it, dodge it, burn it, and you could make a whole different world.

And that began to fascinate me, that you had the control there. So I would crop and crop and crop until the math was perfect. And I trained myself to look for all the elements of math. And now, at my age, I’ve realised that that’s the name of the game—recognising and making available perfect math. And you can either see it, or you don’t. It’s a weird thing… I guess it’s a gift.

The subject or the narration takes a back seat—you’re showing the math that’s going to appeal to the eye or the brain of the person looking, and then they’ll investigate further. It’s the hook that gets people to look.

So you weren’t bothered about the subject?

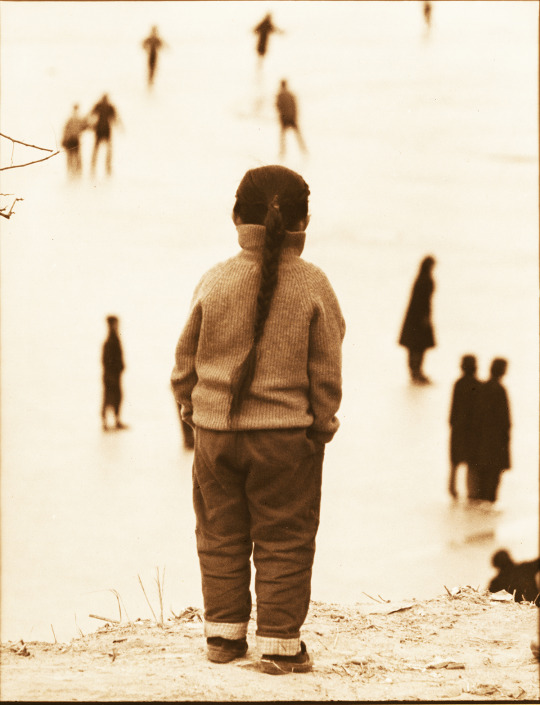

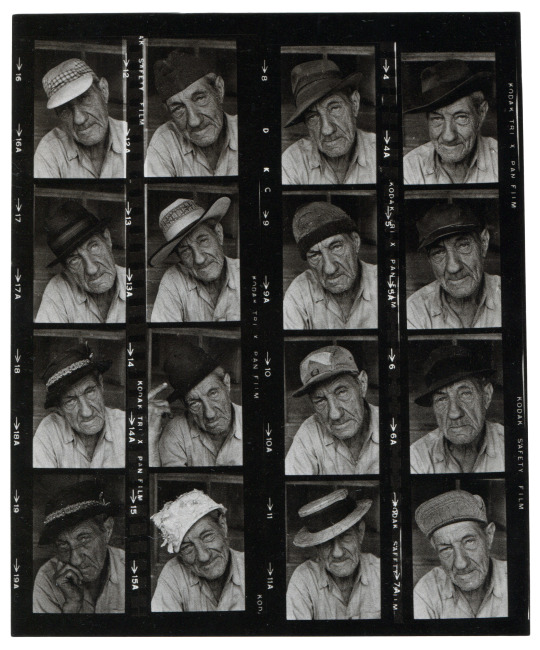

That’s where it started—but looking back over my old prints, I’ve realised that everything I shot early on, I continued to investigate. I love architecture, I love portraits of people, and I love those Cartier-Bresson photos… the non-events… those photos where everyone is doing something, but they’re not related. I loved those. I was always real bold about putting the camera in people’s faces. I did a whole bunch of that. I didn’t ask, and I made a lot of people mad.

Did you get much grief for doing that that?

I didn’t have to fight them off, but I’d have to push them away.

What’s your argument against people being mad about that? Surely the photo was more to appreciate the person rather than condescend.

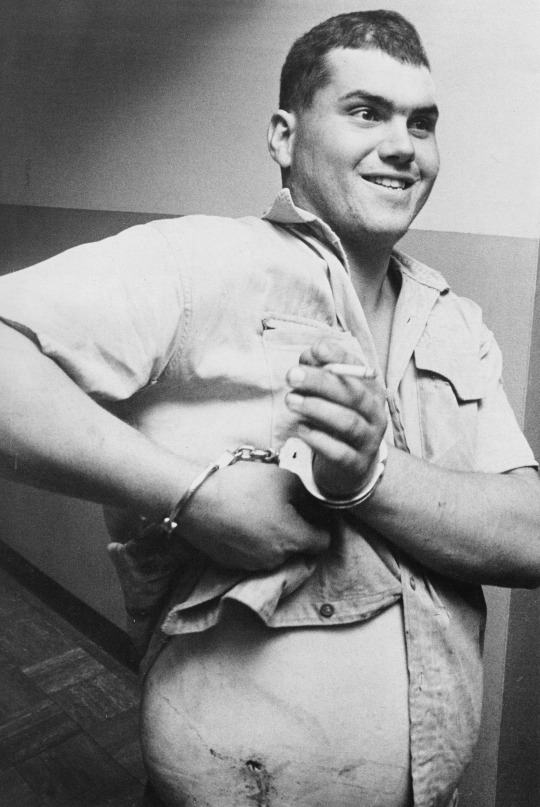

Right, exactly. Or actually, it wasn’t so much to appreciate… I took a lot of pictures that kind of exposed people and showed some of their idiosyncrasies. I liked to do that. I was always bold like that, especially when I was doing a story for the newspaper.

I did television news too. I would always have a microphone in your face… and I had a Nikon around my neck the whole time. I was banging shots and doing interviews. And some of my best work was taken during those investigations for television. I was banging shots whilst I was doing the work—unconsciously. If I saw something and it looked right… BOOM. As simple as that.

Sometimes I think you get an inkling or a hint of what is about to happen. I think that’s what Bresson and those guys did. They were always on the shutter, just before the moment. You had to be ready before the decisive moment. I used to kiss the back of the camera when I’d hold it up to my eye. And then I’d wait and I’d wait and then at some point I’d hit the shutter.

How did you get involved with the news stuff? Did you get into that straight after you got back from Korea?

As a matter of fact I did. The first job I had coming back, I worked as the night-wire editor of an evening paper in Tulsa. I would pull the copy from the AP wire and the UPI wire and Reuters and all that stuff, and put it on the desk of the guys coming in to write about that stuff in the morning. It was an evening paper, but I worked all night long. I had the whole newsroom to myself.

And then after that, I was cleaning swimming pools, and then let’s see… what else did I do? Around that time I built a dark-room at home and I printed a lot of the stuff I’d done in Korea, and put it all together when my father died. That was in ’64. I hadn’t been home very long, so I just packed it all into my ’57 Desoto with push-button controls, and drove 90 mph to New York with all my stuff.

There I worked for a photographer called Vincent Lisanti, he had gone to Brooks, which is a school in California where people go to learn how to use view cameras and super commercial photography. When I got back to Tulsa, I moved into this apartment, and next door was a photographer called Bob Hawks, he’s turns wooden bowls now—they’ve even got a bowl of his in the White House—that’s how good he is, but he’s one eye a photographer, and one eye a bowl carver.

I said, “I’ve just come back from New York and I wanted to see if you needed some help. I worked for Vincent Lisanti.” He said, “Vincent Lisanti? I know him. I went to Brooks with him.” So he gets on the phone to Lisanti and he said, “Oh, he’s great, give him a job,” so he did, and I started travelling around shooting the Sweet Adelines.

How long were you doing that for?

That was about a year, going all over the country. It was great. I’d do the quartet portraits and all that stuff, and then I’d go out and shoot my own pictures. I was just obsessed with shooting.

And then I got a scholarship to go to Tulsa University and photograph their year-book, so I did that—shooting the yearbook in exchange for tuition. And then I just quit and joined the newspaper again, and did television news.

And whilst you were doing this news stuff, you were taking your own photos?

Yeah, but eventually I stopped doing everything and anything apart from taking pictures. But it’s expensive, and where’s it going to go? You get these pictures, but what are you going to do with them? No-one is going to hang them on their wall. It’s not the kind of thing that people use to decorate.

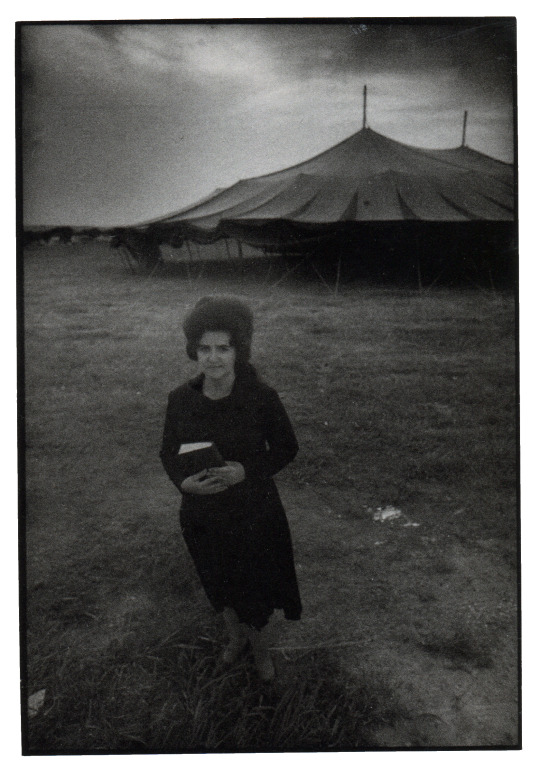

So that’s when Vagabond came along, in 1975. I quit my job to do Vagabond, I went to New York and stayed in the Chelsea Hotel. I think we were in Eugene O’Neill’s old room. Dan Mayo and myself spent a year doing that book.

How was New York back then?

Oh, it was great. I’ll tell you when it was better though… when I went in the mid-60s. The skies were cobalt blue and there was beautiful weather, but then all of a sudden it became smog-ridden.

What was the process for making the book? There’s a lot going on in there.

Yeah, I was using the Cain and Abel story to depict an outcome that was predicted. I was using myself, and my friend Bill Rabon, as examples of the vagabond. And that became a way for me to talk about the dilemma we’re all in right now as modern humanoids.

What do you mean by that?

I think it’s one DNA versus another DNA. There’s maybe 12 DNAs on this planet, and they’re always at loggerheads with each other—that’s my idea anyway. And those DNAs go 6,000 years back to the Garden of Eden… or maybe they go back 60,000 years? They’re all over the lot.

I’d decided that my father had died sooner than he should of, because I had a talk with him a couple of weeks after I got back from Korea, and I started to point out some of his deficiencies—I chewed him out. And two days later, he died. And I always carried that with me, and I’m still carrying that with me. So I did this book for him. He was a vagabond, and I was a vagabond.

When you talk about the dilemma we’re in, what do you mean?

It’s politics, it’s art, it’s war. It’s the dilemma, the debacle. The best example is the chimp—the young males beat each other to death, but they’re almost exactly the same, when it comes down to DNA or whatever, as the bonobo, and they just kiss all day. That’s all they do, there’s no war, they just love all day long. It’s two different wings of the same animal. And that’s kind of what we are. We don’t have enough bonobo, we’ve got too much chimp. And chimps will tear your face off.

Do you think that’s changed at all, since the 70s when your book came out? Will it always be like this?

I don’t know about that. I don’t know about where you are, but around about ten years ago I started having a feeling that we were starting to become dull normals—we were being ‘dull normalised’. You could tell in the advertising and the culture and the thoughts and the way people entertained themselves that they were getting much more like dull norms—like children, just wanting to be occupied and entertained all the time.

Nobody wants to think of better ways to organise our various cultures around the world, and help people out. I think we were much more egalitarian back then. We’re really selfish and childlike now.

AT THIS POINT WE GO OFF ON A TANGENT ABOUT DNA AND ANCIENT ASTRONAUTS. THINGS ARE EVENTUALLY BROUGHT BACK AROUND WHEN GAYLORD SAYS…

…at the same-time, I think the photographers that are serious about photography are called to do that.

Your book wasn’t just photos, it had paintings and writing in there too—a definite departure from the ‘Aperture Monograph’ style of book. How did people react to it?

That book was really well reviewed. I even got a shout-out from Robert Frank.

Did you ever meet him?

Oh no, but I’d have loved to. He was an outstanding photographer. When I first saw The Americans, I loved it. He was going around, shooting in motel rooms, on highways and all kind of things. He was trying to get the atmosphere that goes with it… the dance that goes with it. Sometimes it’s dancing inside and you’ve got to grab it… you’re obligated to grab it.

Where did all that extra stuff in Vagabond come from? How did you go about laying it all out?

Do you know who was going to do it at first? The guy who did that book Somnambulist… who was that?

Ralph Gibson?

Yeah, Ralph Gibson was going to do the book—that was who Dan Mayo was negotiating with, but then finally I said, “Do you know what? I would love to do this myself.” And so I went with it, just starting to wait for ideas… and they came. It was about that simple. It took a year to do it.

And that was the same thing as the photographs… mathematics. When it feels right, the lines are right, the ratios are right, the distances are right, and then there’s texture and colour… when all of that seems to be in balance, like a Calder sculpture, then you nail it, and you get the page.

How did people lay out books back then?

I made a dummy of the pictures and the copy and everything, and then I took it to this guy Sidney Rappaport in New York, the guy who did all the Edward Weston and Ansel Adams books. He was a great printer. He used this triple-tone, it was a lithograph kind of a thing. It was beautiful.

How many did you get printed?

I think there was 10,000. I’ve got about 300 left. People reviewed it very well, which I loved, but it was such a small niche. I tried to promote it as much as I could, but I did a horrible job. I can sell bicycles and I can talk to people until they buy a bicycle, but I can’t sell photographs.

Was there ever plans to do another book? You carried on taking pictures, but as far as I know, Vagabond was your only book.

I’m at the point now where I’d like to relocate the negatives into a collection… a museum or a school or something so they could use it for education. But I haven’t done that yet, so I may at some point try to do a couple of books.

I’ve got thousands and thousands of images, and I’ve scanned in my prints, but until I know what I’m going to do with my negatives, I don’t know whether I’m going to need to print anything else or not. I need someone to sponsor me… it’s not easy.

If you’ve only scanned in your prints, I imagine you must have countless negatives you’ve never seen before. How many photos off a roll of film would you print?

Back in 69 to 71 when I was working at the newspaper I was banging so many shots on a roll that I’d want to print half the roll. It was one after another. I made them on an Ektamatic Processor, which is an interesting aside.

Kodak made this A/B solution roller, feeder and printer. You put your Ektamatic paper in, it goes through an activator, it goes through a stabiliser, and then it comes out, you squeegee it off and set it down and it air dries.

And I made gazillions of prints, just sitting on a stool with that roller printer, and now I’m looking at them, and they’re better now than ever. They were never fixed! Somehow Kodak figured out how to make the chemicals co-exist forever… or something. And these are 50/60 year old prints. They self tone down to sepia over time, as random sulphite molecules attach to them, but the silver is still pristine.

A lot of older photographer has a mystery to it. There’s maybe not as much information in the image, so your mind has to fill it in. Do you think that mystery has been lost a little bit nowadays?

It could be, and it could be that selfies have become ubiquitous and no one thinks about any other form of visual representation. People aren’t doing much because they’re always looking at their iPhone. They’re not getting anything done. It’s seems like as a culture, we’ve made preparation for an accomplishment into the goal. “I’ve got to get all this stuff together, get my money, get all the stuff I need, and then I’ll accomplish this goal.” All the time we’re preparing for everything, we never actually do anything… we’re just preparing.

I think people don’t investigate as much. In an old article, I said that taking a photo was like a stream of water running down a bubbling brook—you reach in and pull out a few drops that you can examine. That’s what a photograph does. It pulls a drop out of the stream so that you can examine it, or identify with it, or learn from it, or even be inspired by it. Or are made comfortable by it. And that’s the beauty of it.

Whose photographs did that for you?

I liked those guys who did the ‘decisive moment’ thing, where you capture it just right. You’d have to be on top of the shutter to get that—you’ve got to be ahead of it. If not, you don’t have it—you’ve just got another dull rectangle. But that’s okay, I think those are important too by the way… they’re just dull.

But I think that permeated my thinking all along. What I was going to say before is that when you shoot that roll of film you were talking about, well, you might have six images on there that you know are good, but then there might be one down at the end of the roll… and you’ll say, “This is it! That’s the shot!” It wasn’t those six—it was that one vagabond image that you saw. You print that puppy and you love it. That’s the one that stands out. You’re talking about various levels and grades of attraction, and math.

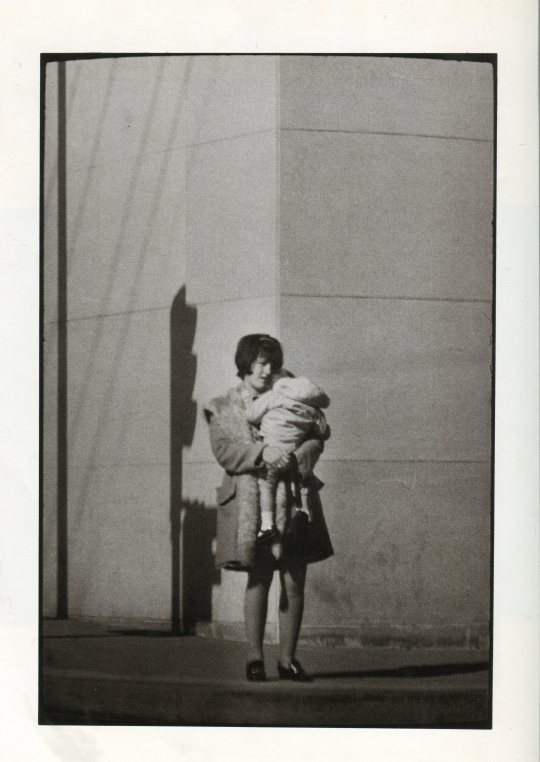

And then there’s content. I’ve always been mindful of content. That picture of that woman holding that girl on that street corner… her face and her body attitude… it makes me cry, every time I look at it, and I don’t know why. There’s just something about the arrangement that touches my soul.

Is that because it’s figurative? There’s always going to be more of an emotion connection to a photo of a person.

Yeah, but those trees… I’m having an emotional affair with the trees right now… but yeah, people come first.

Maybe going off on a tangent here, but I’ve noticed every time you’re mentioned, it’s often in the same sentence as Larry Clark. Is that a bit annoying?

Yeah, there was a review that a woman wrote which compared the two views of Tulsa, Clark and me, and she came out eventually to say that mine was positive, and his was negative.

I suppose his wasn’t really about Tulsa, even thought that’s what it was called.

Yeah, it was about that subculture, the methamphetamine. Whereas I wanted to be as universal as possible. When I was a kid, I’d think, “Wouldn’t it be neat if you could see everything in the world?” And maybe that’s what I’m trying to do—to photograph everything and see everything? But that’s the definition of omnipresent or something, and you can’t have that. But yeah, I thought that’d be neat.

I would just like to see everything, I don’t know why. I do know that it’s a visual thing. I think there’s a speed to your vision. Sometime you can look and get an immediate read from your brain. A lot of times your brain looks at it and says, “What the fuck is this? What are you doing?” But you get this fast, fast read, visually.

I suppose your book is a good example of that mix… of seeing everything. There’s all sorts in there.

It’s a cultural dragnet, over the whole thing. The overarching drag-net.

What do you think about photography now? Do you look at much contemporary stuff?

I wonder about the people who photograph now. They’ve got their iPhones, and they’ve also got their Nikons, and they’re banging shots… but I’m not seeing anything. It might be that they don’t know how to read the culture, or maybe they’re not interested in the things that I’m interested in, but there’s a lot of flamboyance now in art.

I don’t know how to explain it, but I always wanted to reduce it to the basic elements. But now there are all these different things to make it brighter, or make it shiny… we all like shiny things. But right now I’m drawing on this brown craft paper… and that’s what they wrap fish in!

What do you think has kept you going with photography and art and everything? A lot of people eventually slow down or stop, but you’re still at it.

One of the reviewers who wrote about Vagabond said, “I don’t think Herron’s going to write another book.” And he put that thought in my head… but I’m going to do another book—I’m not going to quit just because he said I would. But it was almost like that was my message and that was all I needed to do, and that was pretty much right.

But then I discovered something when Judy died, after that I didn’t go down and print old stuff, and I haven’t been taking pictures the way I normally do—I substituted it for drawing. But I can’t do that forever, so I guess from now on what I’ll do is collate what I’ve done, and try and make it accessible as a teaching tool. But I’m not having much luck with that. That’s why I’m selling bikes.

How did you get involved with that?

It was my son. He had a job in a bike shop, and he wanted to go skiing, so his boss said I could run his bike shop whilst he was skiing. And I just fell in love with it. And we’ve had this place for 22 years now. I grew up helping my father with his business, so I knew about mechanics early on. I made my own everything—whatever I needed, I built it. So this is a hangover from that. And I love the people who come in the bike shop. This is how I maintain my contact with people. But I’m not maintaining my art, and I think it’s because I was doing it for Judy. I couldn’t wait to show her a print. I was trying to impress her, and all along, through all those decades, she supported me—she kept me going. I’d print endlessly, with sepia tone, stinking up the kitchen… and I did it for her.

But now I’m re-organising, and rethinking all of it. And right now, I’m loving the idea of drawing on craft paper. And at the same time, I’m putting a little gallery upstage, showing some prints upstairs.

I might be wrong, but you seem like a fairly deep thinker; what do you think life is all about?

I think we’re here to reproduce, and to help what we produce. We’re here to survive and to thrive. I think we get tweaked up and down from time to time as well. I think it’s pretty simple really.

We’ve got so much energy flying around the planet at all times. There are all kinds of frequencies and wavelengths, and all kinds of lanes, and some people can pick up on a lane, and some people can’t. I keep thinking of Einstein, he’s drawing on a blackboard and doing all these calculations, and he’s in a lane that nobody knows about. But that stuff, the math, is there all the time, you just have to know how to grab it. And I guess taking pictures is maybe a practice of grabbing it. You’re grabbing the math and your brain is interpreting the math.

Were there photos you wished you grabbed? Some that got away?

Oh yeah, there are a bunch of those. But like I say, there’s always that one down the end of the roll that makes up for all the bad shots—all those dull rectangles. I love to look at it when it’s on those proof sheets, I can see the math real easily when it’s reduced down like that. In fact, it becomes bolder in terms of the contrast and the shape. When you’ve got one, you’ll see it, and it’s always that sleeper that you didn’t think of.

I don’t make wet-prints anymore, I do ink-jets. I really don’t like it, but I do it anyway. There’s something about looking into that silver. Silver is eternal, and it’s going to go thousands and thousands of years on that paper. It doesn’t diminish or dissolve or anything, it’s solid, and it stays solid. It’s a very mysterious thing, it’s hard to describe, there’s a luminance that reflects back to you.

Has the computer screen ruined that?

What did Marshall McLuhan say? “The medium is the message.” That’s what I think about all those pixels running around. It just looks like faux… faux life, faux everything. But when you look at silver, you’re looking at a solid piece of material that’s been around for hundreds of years. It’s completely different.

Yeah definitely. I think I’ve got to go fairly soon so I’ll try and wrap this up a bit. What have you got on this afternoon?

I’m actually going to go upstairs and work with photographs, and then do a little work for the bicycle shop. I’m G. Oscar Bicycles in the bike world, and then I’m Gaylord Oscar Herron in the art world. I can maintain both of them though… I can chew gum and walk at the same time.

Do you think it works well together?

Oh yeah, there isn’t anything that I don’t do anymore. I keep them all separate, but it’s all one flow. The whole thing is math.

It all comes back to maths doesn’t it?

The best example of math is this; you’ve got the guy playing baseball, he’s out in the left field, and he hears the ball hit the bat and his mind records the sound. And then he sees the ball leave the bat and coming up to his right, so immediately the eye sends that into the brain and the brain looks at it and says, “Okay, start this leg and this arm and move as fast as you can into the direction that the ball is going to go to, so that you can catch it”. Think about how many calculations that is. It’s all mathematics, it really is. And then he can catch the ball with his glove. And that’s the best example of how math determines everything we do. It’s all mathematics.