-

-

Roman Candle Issue 2

Only three years after issue one, the second issue of Roman Candle magazine is finally done. Sticking with the vague theme of ‘stuff I find interesting’, this one features…

— An interview with photographer Chris Shaw about his stint as a night porter and the alchemy of the darkroom.

— A chat with artist Dick Jewell about found photos and club culture.

— A conversation with E-Man from the notorious NYC bike messenger crew, the X-Men.

— An interview with photographer/film-maker Harvey Wang about capturing the overlooked side of New York.

— Bongwater/Shimmy Disc man Kramer on debunking the paranormal and the time Peter Hook took him for a spin around the back streets of Manchester.This is all served up alongside short stories courtesy of Alex Appleby and Harry Longstaff, a brief chat with Jonathan Richman about his side-job making bread ovens, some words about Bob Dylan from Rivendell Bicycle Works main-man Grant Petersen and some spiel about the mysterious 35mm photos which have been adorning Jandek record sleeves since the 70s.

Available direct here, the central library site, Rare Mags, Village, Unitom and Catalog.

-

The Whistling in the Dark – Trailer

Trailer for the Super 8 bike film I’ve been lazily cobbling together for the last ten years. The Whistling In The Dark should hopefully be finished this year.

-

An Interview With Lloyd Kahn

It wouldn’t be a wild overstatement to say that the Whole Earth Catalog might just be one of the most influential publications to come out of the counterculture movement.

First published in 1968, this printed database of items and ideas—featuring information on pretty much everything you could ever need, to help you do pretty much anything you could ever want—was a vital resource of the pre-internet age, famously described by Steve Jobs as ‘Google in paperback form’.

Lloyd Kahn was one of the key figures behind it. As ‘shelter editor’, he was responsible for the parts of the catalogue devoted to buildings—writing about the tools and methods needed to put a roof over your head.

But the Whole Earth is far from the whole story for Kahn. Taking inspiration from Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome concept, in the early 70s he created Domebook—a vital tome for those who wanted a dome as a home—before turning his back on the hemisphere to publish perhaps his most famous book… Shelter.

Released in 1973, this unique book was an oversized, info-packed guide to DIY house-making that has sold over a quarter of a million copies.

Even that isn’t the full story. More than just a writer and publisher, he’s also a skateboarder, bike rider, surfer, carpenter, forager, gardener and about 500 other things—and whilst he might be 88 years old, he still lives with the same curiosity for life and the world that made his work so inspirational in the first place.

I caught him whilst he was watering the plants in his greenhouse to talk about life in the 1960s, working on the Whole Earth Catalog and how he’d make a house today…

Read the full conversation here. -

An Interview with Kennedy magazine main-man Chris Kontos

For over ten years now, Chris Kontos has been making Kennedy Magazine.

A true labour of love—Kennedy is a rare magazine that favours in-depth conversations rather than endless advertorial spiel. Put simply, it feels like it’s made by someone who actually has an interest in things—and whilst Chris’s taste is maybe a bit more high brow than mine—I really like the simple, honest nature of his mag.

here’s an interview with him. Read it if you want…

I interviewed you maybe six or seven years ago for Oi Polloi, when you’d just finished the fifth issue. Eight issues later, how has making Kennedy changed?

Oh man, that feels like another life. That issue stands as one of the best for me. I met Pierre Le Tan for it, he made a cover for us. I met my teenage hero Lawrence from Felt, we had Tina Barney on it. So many things have changed since. I remember being at Pierre’s funeral in Paris, drinking rum from paper cups in his apartment. Now it doesn’t exist anymore. What is left from reality sometimes? Just the subjective memory of an event?

At least I have some photos from back then. I have the magazine—I’m still making it—now it comes out almost every two years. We went through a pandemic, I went through depression, a break up with my wife. Now that I got out of it, I feel like it makes sense. I feel there is so much ugliness around us and so much hate that I just want to show beauty.

If I made a new magazine now I would make Vanity Fair like Gaydon Carter did. I would want to live in lavish apartments with padded walls and fitted bunk beds for the kids. I know it sounds irrelevant to the question but it’s not. The way I was making Kennedy changed completely. It became me. So much that it’s overwhelming. Our last issue, Family, is the most personal to date. I feel I want to go back to the old way I was making Kennedy, which was more about other people—about their lives, their homes, their morning routines and vices—the things they love.

I like Kennedy because it seems like the product of your interests, rather than an attempt to jump on the coattails of whatever we’re meant to think is cool. How do you formulate an issue? Is it just a case of hunting down the stuff you’re into?

That was always the case, but when I switched to making themed issues since the Greek one that kind of changed. Particularly during Covid and its aftermath I felt the magazine should have more significance and more weight. Now I’m back to where I was ten years ago, closing a circle. I want the Journal of Curiosities back—the list of weekly obsessions—and more people. I want to do interviews again.

A strange phenomenon I’ve noticed is that a lot of people start projects like magazines or zines or whatever almost as a way to get a job, and then once they’ve got hired by a brand or something, they pack it in—but you’ve kept Kennedy going for years now, even whilst doing some pretty high profile photography stuff. What keeps you making it?

Woody Allen once said that we are like sharks—you have to keep swimming, because when a shark stops swimming they die. I just do it. It’s part of me now. And trust me it’s so much work these days, it’s so expensive to make that I would gladly stop. But still something makes me keep on.

And to be honest Kennedy never got where I wanted in terms of work. Still I feel I’m an odd case of a Greek guy making pictures and a magazine that only a handful of people really know. Yet making Kennedy is an honest thing. I keep my integrity, my human side. I strip my self in front of my readers. Some appreciate it and for those I have to keep on doing.

Apart from a few very select adverts, Kennedy is refreshingly free of marketing. How do you keep it pure like this? Do you turn down stuff that’s not right for the magazine?

All the ads in the magazine are from friends with small brands most of the time and independent. I don’t have offers from others to be honest so keeping it tidy and true is easy.

Is lack of funding almost a positive with something like Kennedy? I suppose it means you can make it exactly how you want, and when you want. I can’t imagine you could make something so personal and unique if you had some investor breathing down your neck.

I would never sell Kennedy. And I would turn down any investors. I’ve been indie from day one. Kennedy is me, my personal effort, my release valve. In life you choose either the hard way or the easy one. The easy always sucks, trust me. It might look appealing but in the long run it’s going nowhere.

I do a lot of interviews, and I think whilst this might sound a little strange, I think part of it is because I want to somehow be a part of these people’s lives for a while. Is that the same for you? Do you get a buzz out of capturing these people and documenting them?

Hmm not always—not everyone’s life is as good as it looks and most of the time I would not want to live like them. But with many I felt that I befriended them for a while, and with many I kept a routine of meeting them through the years.

I would always meet Whit Stillman in Paris for a coffee, and I had an ongoing correspondence with Michael Lindsay Hogge. I remember when we watched the Get Back documentary with a friend I told him at the point that Michael appeared with a cigar, ‘’He is my friend!” I emailed him and told him I saw him on the screen with that cigar and he replied, ”I was a big cigar smoker then, Christos. Nobody seemed to mind in 1969 or 1979…or 1989.’’ I could put that on a T-shirt.

When I look back at some of the interviews I feel like for an hour or so I got close to these people and much of what we discussed still resonates.

Do you have a favourite interview you’ve done? Are there ones you look back at and think, “How did I pull that off?”

There are few, like Lawrence from Felt. I ran into him in the street in Covent Garden and I talked to him. He liked my bag and agreed to meet me a week after. We had a meeting at the Barbican but he did not show up. I kept waiting and he came just to tell me he could not make it today and to rearrange for tomorrow. I was like “Why didn’t you just text me?” but he had one of those burner phones that don’t even text.

The first interview I ever did was with Whit Stillman. Then there was Andrew Weatherall, and definitely up there with my favourites is Griffin Dunne.

You’ve done interviews with quite a few people who’ve since passed away—and in some cases your interviews and articles might be the most concise telling of their story available. I’m not exactly sure how to word this question, but is documenting people and places before they go something you think about?

A lot of people we have interviewed in Kennedy have passed, it’s true. Pierre Le Tan, Lawerence Weiner, Philip Perlstein, Ted Bafaloukos. I never thought about it. What I think is at least I got to know them. Their words documented. I feel there is a cultural gap now. All these people go but no one to replace them. The future is cancelled as Mark Fisher said.

What about the interviews that haven’t happened? I’ve got a long list of people I’ve tried and failed to get interviews with. Who has slipped through the Kennedy net?

There were a few I had tried, and although there was progress they never happened—most notably Keith Mcnally from Balthazar. I still have the questions somewhere—I think they are some of the best questions I have put down on paper. William Eggleston too. But the person I still want to feature and have not is Elein Fleiss, the founder of Purple. For me the first issues of Purple are as close to perfection as anything can be. A group of people and their friends doing what they like and became the staples of a whole industry. Tahashi Homma, Mark Bortwick, Camille Waddington. I always go back to these issues for inspiration. I would love my next issue to be like that.

What makes a good interview? How do you make something that stands out from the landfill of unreadable ‘content’.

I don’t know. I guess being at ease with the person you talk to is the key. And be spontaneous. Also having some sense of humour? I remember watching an interview with Fran Leibowitz in Athens—I left before it even ended—it was horrid. The interviewer, who was kinda woke, was trying to make silly jokes with Fran, who is the opposite of woke, and that resulted in some uncomfortable silences. You have to respect your subject.

Haha that sounds terrible. I’ve been to some awkward Q-and-A’s in my time. We’ve talked a bit about this before briefly, but you seem a little… pessimistic for the future of humanity. Is there anything out there that gives you hope out there in the cultural wasteland? What new things do you like?

I’m generally a person who believes in people and I’m not pessimistic by nature, but right now I believe it’s dark—too dark. Everything seems bleak—not just what happens around us but mostly how people perceive them. Everyone is angry. I have never seen people that angry—people with moderately good lifestyles, decent jobs, money and freedom being so angry about everything.

I guess reading old Vanity Fair issues or Graydon Carter’s Air Mail does help me decompress. My family. Michael Heiny’s articles in particular strike a chord always. My own small universe of high end sound systems and expensive power cables so I can listen to mono recordings of Chet Baker. Going to the gym. A good wine once in a while. Thinking about the new issue of Kennedy. And the audiophile wine bar I’m about to open.

I sort of gave up on modern music a bit maybe ten years ago, but I’ve been trying harder recently to find interesting new stuff and I’ve been enjoying it again. What new stuff—be it music or films or clothes or movements or whatever—do you like? How do you look for it?

No matter how much I preach about how bad social media is, I’m an Instagram addict—my saved posts are always a good mood board for living and creating, along with recommendations from friends, Popeye magazines or Brutus. I like Uniqlo’s online magazine too.

With cinema I kinda gave up on western movies a while back. I’ve solely watched Asian cinema for many years now. I think my highlight was Kore Eda’s Broker last year. From the last few years I think Right Now Wrong Then from Hong Sang-Soo was my favourite. I love most of his films. They are candid and true. I miss that in life and movies.

My favourite record of the last few years is Vulture Prince by Arooj Aftab. I don’t buy so much new music because I’m obsessed with jazz and oddities from the past most of the time. Pharaoh Sanders’ eponymous reissue by Luaka Bop was a good one.

As for clothes, I’m mostly selling them. I try not to buy that much. Also the weather is constantly warm in Greece so there aren’t many chances to wear sweaters or jackets. Occasionally I like a nice pair of shoes, I recently got the Salomon Alpage collaboration with Broken Arm. I always like Drake’s and their blazers, a nice pair of denim. Keeping it simple and minimal as possible.

Going back to your thoughts on today, why do you think people are so angry?

I think being angry is existential right now. Yes, we live in challenging times for sure, but people have had it worse in the past. Even 20 years ago, just count how many warzones there were. People find comfort in being upset right now. It gives them reason to define themselves—I live therefore I’m angry. Also there is an obsession people have with the end of history—that we are in those days—it’s an infatuation with disaster. I guess in a Freudian explanation it has to do a lot with mortality and the fear of it—just see how much people like horror movies.

I WAS TALKING WITH A FRIEND FROM MOSCOW RECENTLY DISCUSSING HOW LEFTISTS IN THE WEST SUPPORT PUTIN. WHICH IS ABSURD. I ASKED HIM WHAT HE THINKS THAT IS WRONG WITH PEOPLE. HE SAID “They don’t know what to do and the feeling they can’t change anything is tough. So all they have is that possible sense of being a better human than the rest.” Which is a very wrong feeling in its core (and actually connects them with their so called political enemies. on a level they still can’t understand) In the end I think it’s just virtue signalling. What saddens me most is the fact that there is no dialogue anymore.

You have people who live in the west who are privileged, educated and can consume almost everything that modern culture has to offer, but they are not content. They will find meaning in supporting theocracy in a country in the Middle East, but they are not fond of religion themselves. The plot is lost. I know many people hate Morrissey now, but I saw an interview with him recently and he said being inclusive is the biggest form of conformity. Think about that.

You mentioned Mark Fisher before and his ‘future is cancelled’ quote. How do we un-cancel the future? How do we steer the ship around?

I think the system had to be reset. The only way is to try with any means we have to spread as much beauty as possible to people—to make people engaged—but looking at younger people now I’m losing hope. They have an attention span of seconds and they are not interested in what happened before them. From music to history, they are just not into it. It’s not relevant. I guess if Tik Tok is your only reference it’s hard to know history or even what was relevant 10 years ago.

A nationwide survey in 2020 among Generation Z and millennials showed a ‘worrying lack of basic Holocaust knowledge’ among adults under 40, including over one in ten respondents who did not recall ever having heard the word ‘Holocaust’ before. I mean these things are scary, they will not make me really hopeful.

Mark Fisher has influenced me a lot when dealing with the idea of the cancellation of the future. And it has to do a lot with the fact that the system we live in—mainly a capitalist society—has hit a hard ceiling. It’s funny how the system is using millennials as its tool, social media was the biggest ally to the system ever created. Hipsters unknowingly but willingly serve as the zealots of the system. Fisher was pessimistic and ended up killing himself. He said that movements stopped happening, especially counterculture. For instance he thought Jungle was the last one. In a way it’s true. I would go as far as saying dubstep was the last. Now what? Name me a music movement that means anything to anyone.

Funny story: a young guy who used to come to my gigs and loves Kennedy once invited me to a reggaeton party. I found out it’s huge in young people. I didn’t even know what it was. If they are having fun it’s fine by me, but it won’t change history. Still I want to keep my optimism alive. So many young kids read Kennedy and relate to many things I’m saying or suggesting. Even if only I could influence one person I would still be happy knowing I changed somebody’s view of the world.

Does this search for beauty extend to your photos too? Are there certain things you try to avoid in your pictures? Walking around Athens with your camera do you find yourself drawn to certain places or areas more than others?

It surely does. I don’t take many pics—I’m not one of those people that takes pics on a daily basis. I guess having a phone handy and film being so expensive is an excuse for that but generally I need to be really inspired to take a picture. I won’t go out to take pics if I’m not motivated. I think the best way is to always have a camera handy—the best pictures are always unexpected. I have thanked myself many times that I carried a camera with me.

What do I avoid? I don’t know—I try not to take the same pics twice. Eggleston once said that and I’ve followed his advice since. I try not to take picturesque pics. Getting drawn to things because of beauty sometimes is tricky. In Athens I try the opposite—and not get forced into taking a pic because everything looks so much out of place. I like taking pics around Omonoia, on the way to my new home across Acharnon street. The underbelly of the city.

What’s the situation with the wine bar? It sounds like you’re already pretty busy, what made you want to get involved with wine?

You are the only one I have talked to about the wine bar so far in public. It’s moving—quite slowly—but it’s moving. I’m terrified really—I have been losing my sleep from stress! There are so many things to take care of—I’m just a helpless romantic, not a businessman, but I hope magically it will all work out in the end. Like with Kennedy in 2013 it’s another big risk ten years later.

The reason I wanted to make the bar is to make an audiophile place where I can enjoy wines I can’t find in Athens. My main inspiration was my trip to Tokyo in 2019 and its wine bars—like Wine Stand Waltz and Ahiru, and the listening bars like Eagle, Big Boy—along with a certain wine bar in London called 40 Maltby Street which is a firm favourite.

I like ‘natural’ wines and wanted to make a place where you can enjoy a glass or two. I used quotation marks on natural because most of the time these wines are atrocious—it’s not easy to get the good ones. In the past I wrote some heated articles on wines without sulfites. In my case I hand pick all the producers and I import everything from France. I try to have producers that I know and have visited. All with love. There’ll be listening nights with certain records like a nice event, where people can really enjoy music.

Sounds very nice. Wine bars… magazines… films… are they all kind of the same? This might sound a bit fancy, but are they all about creating a world—sort of building an alternative universe?

We have to create a shelter from the storm. The world is so bad out there we have to save ourselves with wine and beauty—Be intoxicated constantly with love, art music.

Find out more about Kennedy here.

-

An Interview with Jo Scarr

Everyone’s definition of adventure is slightly different. Most are content with an afternoon hike—some prefer a week in the Alps, and for a few brave souls like Jo Scarr, it means something a little bolder—like driving a Land Rover all the way to the Himalayas and hiking straight into the unknown.

Setting off in the summer of 1961, the Women’s Kulu Expedition saw Jo and her friend Barbara Spark—both just in their early 20s at the time—pack up their home-made tent and drive from North Wales right across Europe and into Asia, before parking up in the Indian Himalayas to explore an uncharted region of the Kullu Valley (the second ‘l’ was added later).

In the weeks that followed they not only mapped out an area where no human beings had set foot before but, along with their porters, they scaled mountains that people didn’t even know existed—reaching untouched summits over 6,000 metres high. A year later, more first ascents followed when they joined the all-female British Jagdula Expedition—exploring the isolated Kanjiroba Himal region of Nepal and scaling no less than seven unclimbed peaks.

And this is just the tip of the mountain, with Jo’s CV also boasting the first female lead of the notorious Cenotaph Corner in Llanberis Pass and a lifetime of pioneering archeology work. She also happens to live just down the road from Outsiders buyer Josh—which is why one Saturday morning we found ourselves sat in the ‘mountain room’ of the 500 year old house she lives in with her husband Nigel Peacock (another legendary climber), enjoying a cup of tea and a plate of biscuits as they regaled stories of hiking in the Himalayas, cooking moths and abseiling down university buildings…”

Read it here… -

THROWING POTS AND RUNNING UP HILLS

Recently spent a morning with Percy Dean (of Document Magazine fame) as he threw some pots and then ran up a hill near Stalybridge. Read the article here if you want.

https://kavu.co.uk/blogs/scrapbook/a-kavu-day-with-percy-dean

-

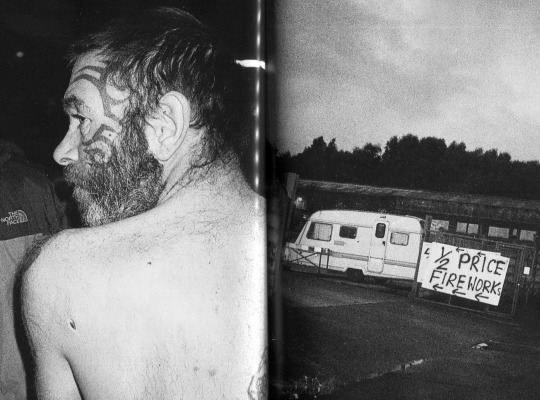

½ Price Fireworks Photo Show

Firing up the laser printer to show some old and new photos on the walls of Cafe Blah in Withington next Saturday alongside fellow lurkers Alex Appleby, Clarky, Gaz Hunt and Louis Loizou. Saturday the 19th from 7pm – come down…

-

Two New Zines

Just finished two new chunks of paper.

Greater Manchester Dark Ages is 164 pages of black and white photos from around Greater Manchester from 2011 to 2015, whilst World Force is 44 pages of phone snaps captured mostly last year.

Both are available via Central Library worldwide, Rare Mags in Stockport, Good Press is Glasgow and Village, Unitom and Catalog in Manchester.

-

An Interview with Grant Peteresen

Grant Petersen has done a lot for the humble bicycle. First through Bridgestone USA (the North American arm of the massive Japanese tyre company who produced some seriously influential bikes in the 80s and early 90s), and then with Rivendell Bicycle Works—the company he started in 1994—he’s been pushing for what you could maybe call an alternative bicycle future, where enjoyment, practicality and longevity take precedence over gimmicks, fads and The Next Big Thing™.

This might sound like common sense, but at a time when mainstream bikes have become unrepairable masses of high-tech jiggery-pokery, his ideas around hard-wearing steel frames and good ol’ simplicity (alongside the countless other uncomplicated concepts he laid down in his 2012 book Just Ride), have set him apart as a revolutionary.

What’s more, whilst his so-called ‘velosophy’ is no doubt influential (the recent uptick in baskets and swept-back handlebars being bolted onto old steel mountain bikes can probably be traced back to him), the way Rivendell operates is also well ahead of the proverbial curve. They’ve sold straight to their customers since the mid-90s and were publishing their own zine, the Rivendell Reader, long before people in meeting rooms started chatting about content marketing. He might also be the world’s biggest Bob Dylan fan.

Anyway, enough of the spiel. I caught him before a fishing trip to peck his head about everything from the early days of Rivendell to the art of finding satisfaction in struggle. Whether or not you’re into bicycles or not, Grant’s wise words here should give you something to think about…

-

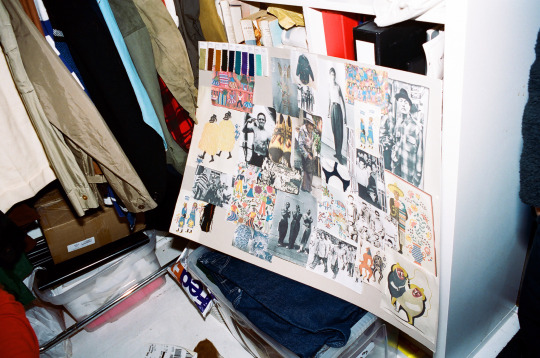

He Did Create – an Interview with Fraser Moss

Gutted to hear of the recent passing of Fraser Moss. I had the pleasure of spending a day with him in 2018 and he was a true fountain of subcultural knowledge who knew everything about seemingly everything good in life—with conversation ranging from vintage military jackets to the third season of Twin Peaks with no let up.

This interview from an old magazine we made at Oi Polloi captured a small portion of that conversation, telling his story from his beginnings in the clothes industry getting sacked from World’s End to flogging rare trainers before anyone knew about rare trainers, starting YMC and beyond. He had a lot of good stuff to say which applies today. RIP Fraser Moss. He did create.

Founded by Fraser Moss and Jimmy Collins back in 1995, You Must Create (or Y.M.C. to give it its snappier title), has been a firm Oi Polloi favourite for donkey’s years. It was one of the first things we sold in our old Tib Street shop back in 2002, and although a fair bit has changed in the world since then, their trademark blend of stripped-back design, high-end fabrics and left-field cultural references is still as flavoursome as ever.

Fraser is the man who designs the stuff. Curious to hear the yarn behind the garms, I made the perilous voyage down to Brighton to hassle him with some questions..

Starting from the beginning, where did you grow up?

Newport in South Wales. I grew up in that period when youth culture was really important, and it was all led by music. I was too young for punk, but I was old enough to recognise it. At that time it was more that post-punk thing – we could see what was happening up in Manchester.

There were only two magazines you could buy which involved style – I.D. and The Face. And you couldn’t even get those in Wales. I had to subscribe to them like some saddo, getting them delivered to my mum’s house. You were limited on the knowledge you could gain.

How did you end up working with clothes? Was it something you were always into?

I was working in a sports warehouse. I was working there and thinking, “I’ve got to get out of here.” So I’d get the coach up to London, and in those days it was all about the Kings Road. I used to go up and down there trying to get a job. I ended up getting a job at Vivienne

Westwood, at World’s End. It was just after all the Seditionaries stuff, so it was like a dream getting to work for her. But then I got sacked because I got pissed up and fell asleep on the counter – someone came in and robbed half the shop. So then I started Professor Head, which was dealing in old school trainers.

Was anyone into old trainers then? That must have been a relatively new thing at that time.

It was just us and the Japanese. We’d go to the library and get the Yellow Pages for a district of America, then sit there all afternoon ringing them up to see if they had anything. Then we’d get on a plane, hire a van and then go around Boston or somewhere.

You’d go into the basement and they’d have full stacks of Jordan 1s and the Wally Waffles. And they’d be selling them for two or three dollars a pair. We had this little office in Soho and a stall in Camden Market, and we’d just sell to the Japanese. It was good while it lasted. I wish I’d taken photos, but no one had cameras – no one cared.

How long did you do this for?

Until our addictions collapsed the business. By 94 it was going tits up. In 95 we started Y.M.C.

How come you started Y.M.C.? What was the thing that set it off?

I was really sick of the fact that the only fashion that was available at the time was big Italian labels, hip-hop or skate. I’m not against any of that, but it was either American or European stuff, and I just felt there was a need for understated, minimal clothing that people could create their own style with. At that time, people didn’t have quality simple clothing—it wasn’t available.

Where does the name come from? It’s a quote or something isn’t it?

Yeah, that’s Raymond Loewy, who did the Shell logo and the Coca-Cola logo. He was one of the first graphic guys who felt he could put his hand to everything. He’d design a logo, he would do architecture and then he’d do a can of soup. He was multitasking.

He did this lecture, and he said, “The thing is, you must create.” And we just nabbed that. At that time it was all very well me being anti-this and anti-that, but I had to do something.

It was a lot easier back then, the world was much more D.I.Y.—but to be honest, apart from the ideas, our first collection was shit—the fabric would be the wrong way around, or one sleeve would be longer than the other. We were learning as we were going.

How basic was it back then? How many people were involved?

It was just me and Jimmy.

How did you meet him?

I met him because he had the same German agent as our trainer shop, Professor Head. We were both disillusioned with what we were doing, so we set up Y.M.C. When we first started it, I was homeless. I’d been dumped by my girlfriend, and I was living on my friend’s floor. And then we got this little office, so I just lived there. It didn’t even have a shower; there was just a tap and a sink. Slowly we built it up so I could live like a normal person, but I remember for a month I was living on Oxo cubes. It was good though, I had a 28 inch waist.

Going back to you in Newport, was there a regional style when you were growing up?

Yeah, particularly when the casuals came along. Every football club had its look. Some might have been more influential than others, so the other teams would copy them. Newport might have nicked this from the north, but we really went for that gentleman farmer look—a deerstalker hat, a wax jacket, some plus four cords and a pair of Forest Hills. Seeing those guys on the terraces was bonkers.

Do you think that regional thing still exists now?

There’s less tribalism. You can be anything you want today, but that doesn’t mean to say you’re part of something. But these guys lived for the clobber and the weekend – it was different. When you’re in that tribal gang, that’s all you know. You’re kind of blinkered.

I imagine you’d get a lot of stick for dressing like that back then.

Can you imagine? Newport is a working class town. You’ve got the steelworks, the mines and the docks. I used to dress up like an absolute clown back in the 80s. I’d wear these opulent Nehru suits, I had my hair long, I had a walking stick and a fur coat. I’d be pissed out of my head, rolling into curry houses at three in the morning and going to sit with a load of rugby boys. You can Imagine the abuse I got.

Do you think that adds to the appeal? You were putting yourself on the line.

Definitely. It’s edgier. Today, I can walk around how I want and no one is going to bat an eyelid, but walk around Newport in the 80s like that and you’re putting your life at risk.

I suppose it’s like tattoos. In the 60s having a tattoo would be a pretty raw thing.

There’s no edge to most things now. Everything is accepted. From antiques to records, everyone knows what’s what. Everyone’s an expert and nothing shocks anyone. You can stream ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ on the internet and then say you’re a Joy Division fan, but it’s only on a basic level, the passion has gone.

I’m an obsessive vinyl guy, but I always have been. When I was young it was only vinyl, and when CDs came along, I didn’t reject them, I just couldn’t afford a CD player. And now I have to deal with my own son telling me that vinyl is fashionable and putting records on his wall. I say, “No, you play it, you don’t put it on your wall.” It’s not a trophy.

I collect records because I want the music. I go to record fairs, and there’s always dirty old fat blokes in overcoats looking for a Japanese import Madonna picture disk – it’s Madonna, what does it matter?

You’ve mentioned a few times about having an edge. How important is that?

It’s everything to me. I have this argument with people all the time.

I’ll say, “Taylor Swift is shit,” and they’lI say, “Yeah, but she’s successful.” But she’s still shit. People in the modern world can’t differentiate success with talent. And that’s why it’s important to have an edge.

What about for Y.M.C. – is it tough to strike a balance between what you want to do and what you know will sell?

Yeah, when we first started it was all about creativity, and ultimately it got to the stage where it was too out there. We were doing turquoise leather tracksuits in the late 90s. We weren’t doing four armed jumpers and hooded underpants, but it was still pretty out there. You’ve got to be creative, but it’s a business, it’s not a folly.

Is it hard not to be swept away with trends and stuff though?

It is, and I don’t want to be disrespectful to anyone who lives in a small town, but if you’re living in a small town, and you’re craving the latest thing, then you’ve only got the internet to tell you what’s happening. But when I was young we had nothing so we had to create it ourselves. And now I just sound like some old bloke.

When I design things, I tend not to look at other people’s stuff. I’m not on Instagram and I don’t have a Facebook account – I’m not totally unaware to what’s going on, but things are as pure as I can make them.

Obviously you’re mad on records and bands and all that. How does that feed into Y.M.C.? People talk about Influences, but I always want to know how they actually affect things.

When we first started, I was listening to Stereolab and a lot of library and soundtrack music. It was that retro-futurism thing – that idea of looking to the past and twisting it to create something for the future has always been relevant. You can’t create a 100% new thing. And it’s the same with clothes – everything we do has a twist on something that has come before – but we’ll never take anything literally.

What do you mean by that?

Well, we wouldn’t just say, “We’re making a hippy collection.” You can use elements from the past, but you’ve got to make it relevant and modern clothes still have to be wearable.

What are your thoughts on that remake angle – people who make clothes exactly how they were in the past?

I understand why that’s done, but it’s just not for me. I want to watch Peaky Blinders, but I don’t want to dress like them.

A lot of the stuff you reference is military or workwear. Why do you think men always come back to these functional things?

Men like there being a reason for something. We just love all that. It’s that idea of the working man. It’s all fantasy – I mean look at me – I look like some Vietnam veteran.

Haha, like Lieutenant Dan?

Yeah, we all play these rolls. You can’t take it too seriously.

I suppose you lot aren’t making clothes for the military, but that functional thing is still important.

Yeah, it doesn’t have to be ballistic, and it doesn’t have to be fireproof. I just think of my mates when they go to watch the football. I’ve got to make sure that if they wear one of our coats, it’ll either keep them warm, or protect them from the rain.

Is it hard to find things to reference? There are only so many jacket shapes out there.

If you’ve spent the last 20 years immersing yourself in it, there aren’t really any surprises anymore. So when you do find something new, it’s a good feeling. A new shape or a shoe no one has seen before. It’s interesting how something can seem outrageous to someone, and then within a couple of years, it’s something they can’t live without. Believe it or not, when we first made a V-neck cardigan maybe 20 years ago, people were like, “What the fuck is that?” But eventually, it registered.

It’s like the cropped trouser. We’ve always done a short-legged trouser. I don’t know why, it’s just something we’ve always done. In Wales we say you need to put jam on your shoes and invite your trousers down for tea. But now look around and everyone is wearing ankle flapping trousers. It becomes the norm.

I remember when I first moved down here twelve years, I had a quiff. And I used to get people shouting, “Elvis!” out of their car windows. 12 year ago, a quiff was seen as outrageous.

Yeah, things move pretty fast. How have things changed for Y.M.C. since it first started?

Computers, the internet, social media – it’s changed everything. It doesn’t matter how much I moan about it, but this stuff isn’t going away. When we started people were still photocopying and using fax machines.

On a deeper level, how have things changed? Are you still trying to do the same thing with Y.M.C. as you were in 1995?

Yeah, we’ve kind of always kept true to our beliefs. Basically, we’ve got the same ethics now as we did when we started twenty odd years ago.

What would you say those ethics are?

Well, it all goes back to the name. You Must Create. All we want to do is create nice pieces of clothing that the customer will want to buy and wear how they want. It’s all about the product.

It’s important that it’s not fickle or trend led. I’d like to think someone could have bought a pair of trousers off us ten years ago and still wear them today.

We’ve rattled on for quite a while now. Before we wrap this up, are there any words of wisdom you’d like to add.

Nah, after rabbiting on for this long, I haven’t got anything left to say. I’ve probably contradicted myself a hundred times.

-

Fancy Goods / operation vulcan

FANCY GOODS / OPERATION VULCAN.

A cartridge of Super 8 fired off in the rabbit warren of wholesale shops, counterfeit gear floggers and reputable curry cafes at the bottom of Bury New Road. Spent a lot of time wandering around here over the years, but it seems like thanks to Operation Vulcan (a police operation which may or may not just be a land grab to bulldoze and peddle this prime slab of real estate just outside of Manchester town centre) it won’t be like this for long.

Undercurrent of industrial dread courtesy of Tom Hopkins.

Best viewed on a snide iPhone with a cracked screen and blown-out speakers.

-

Pastry Chefs and Flat Tire Flyers

Since 1977 cyclist/pastry chef Tilmann Waldthaler had been pedalling around the globe – clocking over 590,000km in the process. I found out about this guy from reading a small article about his adventures in a 90s bike magazine I was scouring through at a second hand shop—a bit of internet sleuthing later and I was calling up an Australian retirement village to talk to him about bikes, kicking back with Bob Marley and nearly getting gunned down in Iran.

Read it over on the Outsiders site.

On a sort of similar two-wheeled note, I recently interviewed Iris Slappendel about her busy life since ‘retirement’ from the pro-cycling world, making clothes, starting up the Cyclist’s Alliance and working as a commentator for Eurosport.

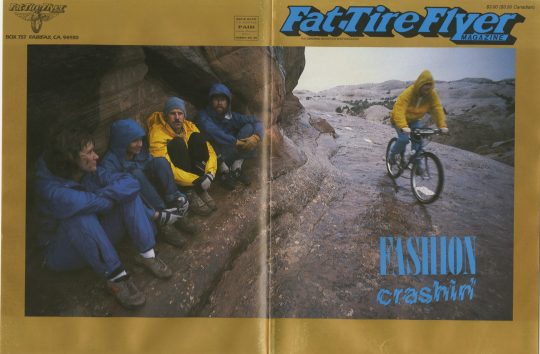

MTB pioneer Charlie Kelly has been uploading some old issues of his Flat Tire Flyer magazine. This thing started out in 1980 as a simple newsletter before morphing into the first real mountain bike magazine, documenting the transition from balloon tired klunkers to honed Japanese machines. The covers are the best things about this magazine, with the limitations of the era adding to the charm.

The last cover is particularly good. Check the old Nike and New Balance runners to the left. Reappropriating what you can find will always be more interesting than forking out for whatever some ‘development team’ decided you should wear. Mountain biking looked infinitely cooler when there was no such thing as mountain biking clothes.

Here’s an interview with Charlie from a decade ago. Time flies when you’re constantly mithering people half-way around the world about things they did 30 years ago.

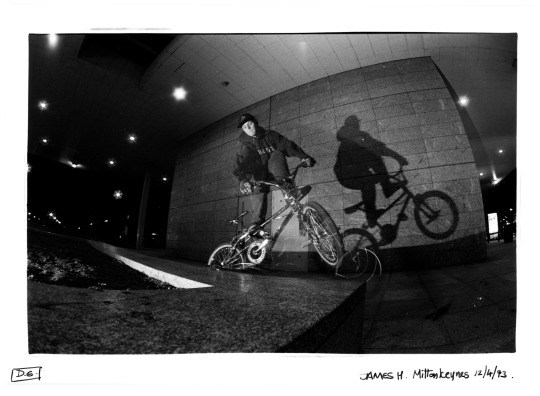

On that note, here’s an interview with photographer, rider and magazine-man James Hudson. From back-garden ramp set-ups to the big-top and beyond, James Hudson spent the 80s and early 90s fully engrossed in the world of riding and skating, not just as a rider, but also as a photographer and magazine-man—contributing snaps to R.A.D., editing SK8-Action and publishing BMX Now. This was originally printed in the last issue of Red Steps but there’s no harm in stuff being on the internet too.

Next issue of Roman Candle should hopefully be out sometime in summer. This stuff takes time.

Until then, here’s 28 minutes of audio mastery courtesy of James Ferraro. Been listening to this one a lot lately.

-

An Interview with Derrick Bostrom from the Meat Puppets

Writing about any music is tough, but writing about the music of the Meat Puppets is really tough. Breaking beyond the noise of the early 80s hardcore scene, this lot scorched ear-drums with a wide-open sound completely their own.

Some called them ‘alternative country’ and some called them ‘cow-punk’, but neither of those weak terms did ‘em justice. This lot nabbed flavours from the full sonic spice-rack to serve up a most flavoursome aural stew.

They’re still at it today, and after a few decades of working ‘a real job’, original drum-smacker Derrick Bostrom is back in the van. Here’s an interview with him about the early days of the band and the realities of being on the road.

Kicking things off at the beginning, what got you into playing the drums? Was there a defining thing that set you off?

I used to play on coffee cans along with my records as a kid. My mom decided to buy me a ‘proper’ children’s set when I was eight, but my kid brother destroyed it after a couple weeks.

When I was 17, I got a cheap department store drum kit so I could play along with a friend of mine who had an electric guitar. I played it for a couple years before I started looking in the newspaper ads for an upgrade.

What sort of music did you listen to growing up? Did playing in bands and being up on stage seem like an attainable thing?

I listened to typical progressive artists when I was a teen. The Dead, Zappa, CSNY, Yes, Todd Rundgren, King Crimson, Eno… and The Beatles, of course. I got heavily into punk in 1977. Once I saw punk rock, I immediately knew I could do it, and started my plan for world domination.

The arrival of punk rock is often talked about as this seismic thing—but as I wasn’t even born then, it’s maybe a bit hard for me to get my head around how radical it was. What was it like for you? Was it a real, noticeable shift?

Punk was seismic enough to make a splash even in a backwater like Phoenix. My friends and I used to get good weed from some cool older guys in town who had turned us on to music like Gong, Eno and King Crimson.

They then got into punk rock, formed bands, got gigs and got local press—I was amazed to read about my friends in the local weekly. Around the same time, I was seeing my first interviews with Johnny Rotten in Creem magazine. I was fascinated. I got caught up in punk quickly after that, though I was alone among my friends, who thought punk was a joke.

How did all this lead into you starting a band?

I tried to talk everyone I knew into starting a band. My friend with the guitar and I had a duo we called The Atomic Bomb Club, but he was hyper-critical of himself and didn’t like performing in front of people. He was also committed to finishing school and getting a ‘real’ job.

Even back then, all I wanted to be was a professional musician, but it wasn’t until I got to know Curt Kirkwood that I found someone interested in the same thing.

How did you lot meet?

I initially met Curt because my friends and I had access to good bud, but he also needed more cool friends. He was a cool guy who lived on the uncool side of town. Eventually, we connected. He was open minded enough to take an interest in my punk rock records, and soon we’d learned a bunch of them. Next, we invited Curt’s younger brother Cris to play with us.

Do you remember your first show?

Our first couple of shows were private parties for friends. We basically ran through songs we’d learned from my punk rock 45 collection. In the summer of 1980, we named ourselves Meat Puppets, started writing songs and did our first club gigs. We were so feral that we blew everyone’s mind.

The second album is the one that gets talked about—but the first one is still pretty wild and unique. What went into the making of that? What were you trying to do?

We got a lot of attention playing so fast and so crazy, but it was hard to reproduce that energy and intensity in the studio. The first album is us trying our best, but we were very green so it didn’t come out as good as we’d hoped.

Still, the first album stands as a good document of where we were at back then. Most of the songs are cranky punk anthems with words by me and music by Curt. Curt avoided the stupidity of my lyrics by screaming unintelligibly. After that, he started writing his own lyrics.

You spent a lot of the early 80s touring with Black Flag. What were those shows like?

Our distaste for ‘hardcore’ audiences is what caused us to turn our backs on punk rock. We took too much abuse from Black Flag fans back in those days. We didn’t like the fights and the spitting and throwing things. We didn’t like the jock mentality. We retreated back to our hippy roots pretty quickly, taunting the audience and playing shit they hated until they stopped coming.

What else went on when you were on tour? I know the shows are obviously the ‘juicy bit’, but I’m always interested in the normal stuff and the down-time.

We liked to spend as much time in nature as we could in between shows. We liked to go to the forest whenever we could. But mostly, it was long drives between towns, begging for floors to sleep on and looking for cheap food.

Do you think some people missed the point with punk music? Were some people just looking for an excuse for violence and dubious behaviour?

Some people thought that violence WAS the point of punk music! We didn’t feel that way, obviously. But people tend to miss the point a lot, no matter what they think.

The music was fairly different, but you lot shared a lot of sensibilities with Minutemen and Hüsker Dü. I’m not sure if competitive is the word here, but was there ever any slight rivalry between the bands? Did what they were doing spur you lot on at all?

We never felt competitive with the Minutemen nor the Huskers (there were times, however, that Cris would become exasperated with my simplistic style and wish he had a drummer like Hurley in the band!) But in general, we didn’t feel like we had much in common musically with our SST label mates. We were just into our own thing too much.

That time in music is often mythologized (maybe I’m doing it right now)—but what are the things that don’t get talked about? What sucked about being in a band in the early 80s?

Doing it as we did, for a living, being in the band left us very broke most of the time. We had to tour constantly in order to make ends meet. This was not only exhausting, but disruptive to our lives. The upside is that it made us a great band.

How involved were you with the song-writing? How did a song tend to come together in the mid-80s?

I wrote most of the lyrics for first songs, the ones on the first album. But once I got the pump primed, Curt took over from there. After that, I contributed song titles occasionally. Since we rehearsed all the time, we usually develop a song over time during rehearsal. As often as not, Curt wouldn’t finalise lyrics until he got a song into the studio.

What about the recording aspect of it? Were there endless multiple takes and mammoth studio sessions, or was it all pretty laid-back?

Each studio session was different. Quite often, our reach often exceeded our grasp in the studio, so sessions could be fraught with frustration. I can confirm that it was never laid back. It would take us a good while to get comfortable in the studio.

Am I right in saying you all lived in a house together? Were you working at the time or was being in the band a full time thing?

We lived together for a while in the early days. Or rather, the brothers lived together and I crashed at their house most of the time. When Curt and his girlfriend had twins in 1983, I moved out. But we always lived nearby one another and were able to rehearse as often as we wanted, usually every day.

Up On the Sun was another fairly distinct record—but it’s maybe a bit more… erm… ‘stylistically cohesive’ than Meat Puppets II. Was there any specific themes or influences going into that album?

I suspect that Curt become a father had the most thematic impact on the album. But also, we’d been together for five years by this point, were always restless, and were itching to spread our wings.

Did you anticipate it becoming the classic it is known as now, or was it just another batch of songs?

I always felt that ALL of our output was destined to be classic.

Haha – fair enough. You lot played at the Desolation Centre Gila Monster Jamboree in the Mojave Desert which is often seen as the precursor to a lot of the big festivals that exist now. What do you remember about that?

It was a long drive out to the middle of nowhere. The PA was terrible. Our performance was just fair. There was a lot of psychedelics around. Kind of a pain in the ass gig.

I like your honesty there. I’m not sure if Mirage is a particularly popular Meat Puppets album – but it’s one of my favourites. For a fairly clean-sounding album, there’s a lot of natural-world type stuff on that album. Did you think much about the lyrics, or were they just things that Curt came up with?

Curt completed the lyrics in the studio. We had a lot of the music rehearsed, but he had a notebook full of stuff that he didn’t finalize until he had to record his vocals. This became a pretty common practice for him after that.

A lot of people dream of being in bands—but not many people actually cut it. How much work is actually involved?

For us, it was a full time job. Constant rehearsal, constant touring, lots of recording, lots of talking to people on the phone, lots of self-promotion. If you put that much into it, you’re bound to get something back, no matter what your endeavor. You don’t even need to be actually good if you put that much work into it, though it helps.

By the early 90s you were signed to a major label and featured regularly on MTV. On the face of it, this is ‘a positive development’—but how was it for you? How did the new business aspect, and the tour bus, change things?

We did a lot of good work in those five years, but it took a toll on our relationships and on our art. Ultimately, I think it pulled us off our game. But we’d been on indie labels for ten years at that point, and were sick of being broke and were near to burnout. Being on a major gave us a nice shot in the arm. Plus, the exposure we got in those years allowed us to keep working right up to this day, during a time where “rock bands” aren’t exactly in high demand.

You left the band in the mid-90s. What else have you been up to since then? Was it weird to work a ‘normal’ job after being a band for years?

Getting married and getting a “real job” saved my sorry ass. It allowed me to grow and mature and explore my potential.

Now that I’m back with the band, my experience in the “real world” is really paying off. I’m a better Bostrom in every way than I used to be back in the day.

You’ve been back with the band since last year. How do you think playing in bands has changed since back in the early 80s?

In too many ways, things haven’t changed at all. The band itself and the music is a lot better. But the Meat Puppets has never been a “popular” band, and just like in the 80s, we can sell out any three-hundred-person-capacity club you can name. But beyond that is anybody’s guess.

Have crowds changed much since back then? Do you think people react to music the same as they used to in the 80s?

Like us, the crowds have aged. But we still pull in some younger folks. By younger, I mean people in their 30s and 40s of course.

You lot seem to attract a pretty obsessive fan-base. People have written books about the lyrics, and I’m sat here now typing up questions about stuff from over 30 years ago. What do you think it is about those songs that register with people?

For one thing, our songs are fantastic. Second, Curt makes sure his songs are open-ended enough to be open to a wide interpretation.

What do you think kept Curt going with the band over the years? He’s been with the Meat Puppets the whole time.

Curt just likes to play. He’s lucky enough to have had enough success to allow him to keep it going at a pace that suits him.

What was it that brought you back into the band? Was it something you were wanting to do for a while?

I reconnected with the band when we were inducted into the Arizona Music and Entertainment Hal of Fame. I hadn’t considered rejoining the band at all before that. But so many people were excited for the induction that I swallowed my pride and reached out to Curt. Once thing led to another after that.

How do you apply your ‘real world’ experience into the band? Rock bands don’t usually hint at a logistical mind, but I imagine it’s pretty important.

Mostly, I have experience working with lots of different kinds of people now. I came straight out of my teens into a rock band, and never really learned that skill. I’ve also learned how to keep organized and stay focused on a a goal. I’ve also learned how to HAVE goals!

Makes sense. I think this is my last question; thinking back to the lyrics and the art that goes with the albums and everything, there’s some funny stuff in there. Is that sense of humour important?

It has always been impossible for the meat puppets to look at the world as anything but completely absurd!

Interview originally published in Roman Candle issue 1.

-

Scrap Cars Wanted

Scrap Cars Wanted is a 40 page zine mostly made up of unused riding photos from the last five years or so.

For anyone wondering, the title comes from a batch of notorious stencilled signs which cropped up everywhere in Manchester around ten years ago. At the peak of my obsession with these big plywood adverts one windy winter night I successfully managed to liberate one from a chainlink fence and bring it home on the train wrapped in bin bags. My sign eventually rotted away, but I’m pleased to say that after a few years AWOL I’ve started to see these things crop up once again – always in the best locations.

Anyway, this zine is the first in the Central Library Editions series. Will it also be the last? We shall see.

https://www.thecentrallibrary.com/product/scrap-cars-wanted-zine-sam-waller

-

In Praise of Army Surplus Shops

Army surplus shops are really something. Not only are they rammed full of dope military garb, but they’ve got a certain raw ’n’ raggedy flavour to ‘em which is missing from most places these days. Like the humble car boot sale or the British seaside town, they seemingly operate on their own axis, relatively untouched by the sanitised hand of modern life.

War-time wares are piled up all over the place… old sheepdogs snooze behind the counter… mysterious scents waft throughout… and amongst all this, the clothes look sick and will actually last for longer than five minutes.

Admittedly they can sometimes be a bit of a gamble, but it’s in that roll of the dice that lies the appeal. This isn’t lazily clicking the ‘add to basket’ button on some slick-looking website and then getting the garb delivered into your lap via drone the same afternoon. It’s an effort, and whether or not you even buy anything is besides the point… it’s an experience that you’ve got to earn. The ‘buying things’ aspect is just a small part of it.

From what I can gather, the blueprint for these fine establishments was first drawn up over the Atlantic after the Civil War. Up until then, most war gear was made in fairly short runs by each separate regiment… but with mass production added to the equation, military schmutter was churned out by the shedload. When the war was over, both sides had plenty of wares to spare, so they set about flogging it as a way to make back a bit of wedge. One of the big bidders was a 14 year old scrap-metal merchant called Francis Bannerman.

Francis sunk his sizeable scrap fortune into buying heavily-discounted surplus gear (guns included), and after a bit of shuffling up the ladder, bought a seven-story super-store in Manhattan to house it all. Aptly-titled ‘Bannerman’s Army & Navy Outfitters’, this shop attracted the attention of everyone from twiddle-tashed gentleman-explorer types to mercenary soldiers fighting in the Spanish Civil War, and at it’s height, needed a full island on the Hudson River, complete with custom-built castle, to store all its stock.

Bannerman’s eventually dwindled for various reasons (including constant explosions on its ‘surplus island’ caused by rusting artillery), and whilst it slowly faded away throughout the mid-20th century, it set the stage for countless other surplus shops to pop up in seemingly every small town around the globe.

From WW2 up until the Gulf War the constant stream of battle meant there was no short supply of hard-wearing clobber, and the growth of arduous leisure activities like camping, fishing and hiking meant that more people were after tough clothes that didn’t cost a fortune. And perhaps most importantly, unhinged small-town madheads who didn’t make it into the forces could now walk their Alsatian whilst draped in the clothing they dreamed about.

These days there are still a fair few of these wondrous establishments around, and whilst a few of them have been infiltrated by snide ‘military-esque’ gear seemingly designed for moody bouncers and paintball moshers, gems may still by found in the shape of old M-65s, ripstop BDU jackets or those US Army ECWCS Gore-Tex parkas (which cost a fraction of the price of usual GORE-approved garb).

As well as the yank stuff, also look out for Swedish military work pants, German cold-weather parkas, that wild Swiss Aplenflage gear and another other Euro anomalies (like the seldom-seen Irish ‘Paddyflage’).

Don’t hang about though—in the age of artificial intelligence and cyber warfare, less humanoid cannon-fodder is needed, and because swanky computers and high-flying drones don’t wear ripstop cotton, not as much gear is made in the first place. Obviously it goes without saying that the less people involved in combat the better… but still, this genuine surplus won’t last forever—snaffle it whilst you can and leave the real combat to the robots.

-

The Stone Monkeys of Yosemite

A few months back I wrote down some stuff about the Stone Monkeys over on the Gramicci website. This lot followed after the Stone Masters of the ‘70s, pushing things further once again by pioneering all-manner of bold outdoor pursuits. Read the full thing here…

https://gramicci.co.uk/blogs/journal/in-profile-the-stone-monkeys-of-yosemite

Illustration by the almighty Ben Lamb

-

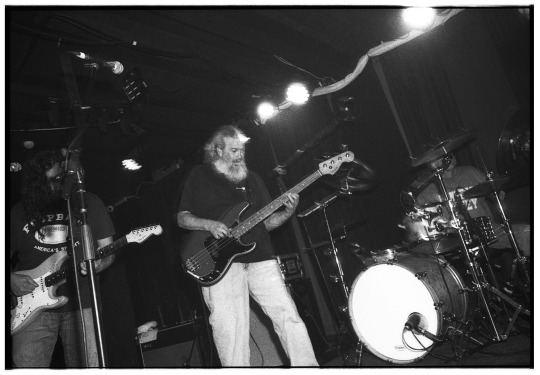

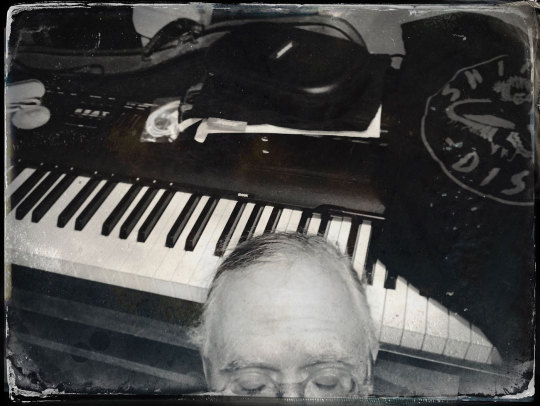

Kramer Obscura

I recently had a phone call with legendary musician, producer and Shimmy Disc main-man Kramer about his new ambient album, his time in the Butthole Surfers and working with Daniel Johnston. This guy has been involved in some of the finest records of the last 40 years, so chatting to him about his work was a true pleasure…

Read an edited version of the chat on the Quietus site here. The full Q and A might end up in the next Roman Candle magazine if all goes well, but this article still covers a fair amount…

https://thequietus.com/articles/31884-kramer-bongwater-interview

-

Unified Goods Interview…

In the present day, the past is easier to grasp than ever before. Whether it’s the AI algorithm serving up long-lost city pop, or the notorious cult films that are only a click away, perhaps one of the main defining characteristics of the current era is our convenient relationship with recent history.

That said, there’s still no substitute for accessing this stuff in physical form, and although it might not take long to find a poorly digitised copy of a Derek Jarman super 8 film on Youtube, or maybe a few low-res scans from an old Face photoshoot on an Instagram moodboard page, these metaverse versions still don’t hold a candle to the real thing.

That’s where Unified Goods comes in. From pristine copies of Perfect Blue on VHS to official Aphex Twin beach towels, the London-based shop sells tangible cultural artefacts from the not-so-distant-past—liberating rare gems from attics and wardrobes around the globe. And whilst niche culture can often be a bit of a closed-off clique, the shop is anything but elitist—choosing to share the knowledge rather than belittle those who aren’t in the know.

With founder James Goodhead currently scouring the streets of New York for new stock, I talked to him about hoarding, Fargo snow globes and nostalgia over on the Sabukaru site…

https://sabukaru.online/articles/unified-goods-using-the-past-to-progress-culture-forwards

-

An Interview with David Keyte from Universal Works

Founded in 2008 by David Keyte and Stephanie Porritt, Universal Works takes cues from sportswear, functional military design, utilitarian work-wear, British tailoring and about a thousand other reference points, to make a range of modern, wearable clothing.

In today’s fractured age—an amped-up era when everything at once vies for your attention, Universal Works has made a name for itself off the back of well-thought-out design—free from gimmicks, but rich in functional details.

In my latest interview for Nativve, I talked to David about the early days of the brand, separating business from creativity and the importance of mixing things up…

https://www.nativve.com/people/an-interview-with-david-keyte-universal-works-co-founder/