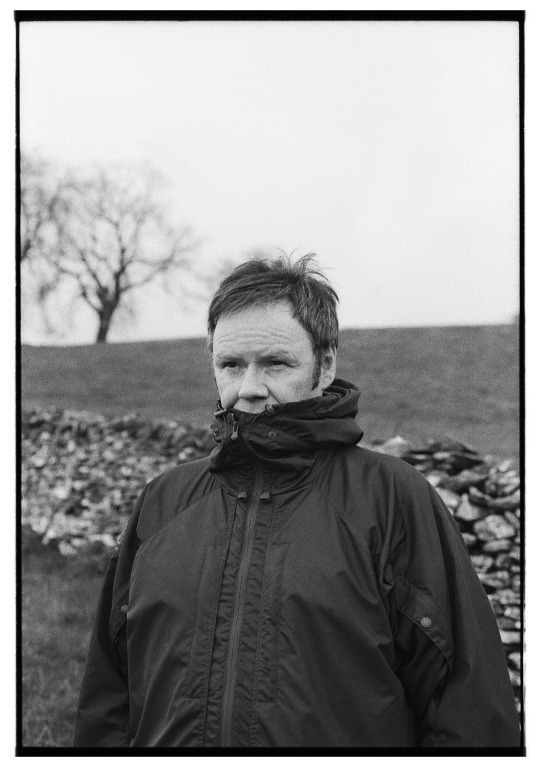

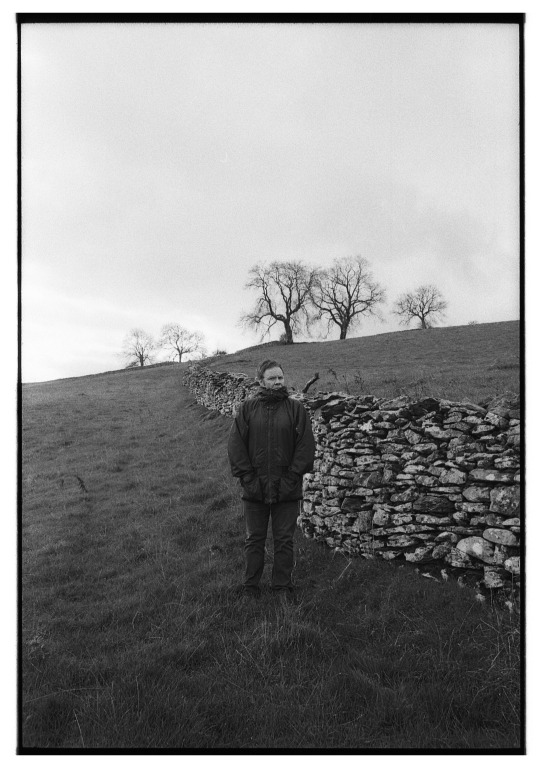

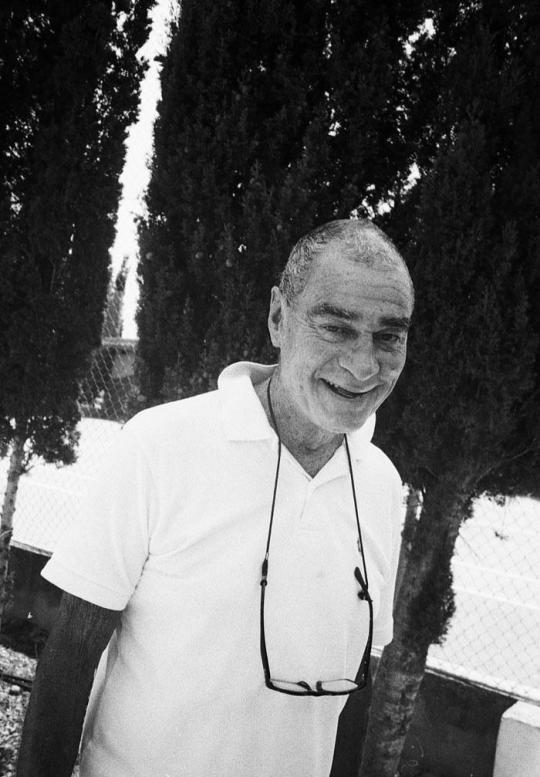

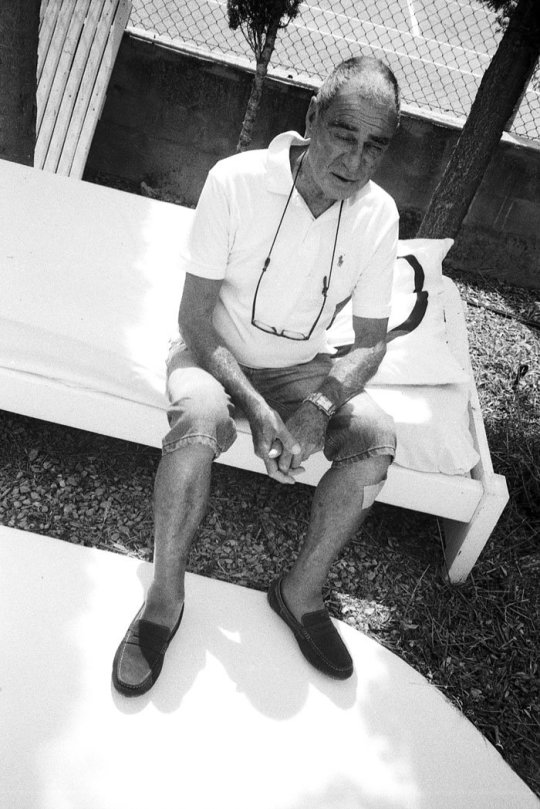

Whilst most humanoids struggle to master even one useful skill in life, John Lurie is one of those adept rapscallions who can seemingly turn their hand to pretty much anything — from acting to angling.

This knack has led to a fairly stacked C.V. which involves such notable achievements as forming a rule-flouting jazz band called The Lounge Lizards, appearing in films like Down by Law, Paris, Texas and Wild at Heart and showing his paintings in exhibitions all over the planet.

And if all that wasn’t enough, he’s also hosted his own fishing show, and, with the help of Dennis Hopper, once came particularly close to snagging the elusive giant squid.

Here’s what he had to say about fishing, New York in the ‘70s and the importance of humour in the world…

First question… your television programme Fishing with John is mint. How did that come about?

I was threatening to do it for a long time, but wasn’t really serious. I would go fishing with Willem and we would video tape it. I flew out one New Year’s Eve to play with Tom Waits and the next day we went and fished with Stephen Torton video taping it.

This woman, Debra Brown, saw the tapes, home movies actually, and brought them to a Japanese company that was looking to get involved in things in New York.

She came back to me and said they wanted to make a pilot. I believe my response was, “Are you kidding?”

When you watch a film or television program, you only see the end result. What was it like filming that thing? Were there any mad struggles?

If you see something good, you can just assume there were mad struggles. If you see something bad, you can assume that people were too lazy to take on the mad struggles.

If I am flicking through the channels looking for a movie, I can tell you in five seconds if a movie is going to be any good by the sound of the door closing or the light or the music or whatever.

Why do you think people love fishing so much?

First off, so we can go to these beautiful places and pretend to be doing something. We wouldn’t go if there were nothing to do. And there is that visceral thing. A big fish on the line is like that exhilarating sports thing, like hitting a baseball perfectly or shooting a basket and the net just goes swish.

And then there is that thing of the world of mystery, right next to the world we are living in. What is in there? We are only going to be aware of what is there with a hook and a nylon string.

So of course we have to drag this amazing creature out of the water and kill it because human beings are pretty much ridiculous. The last bit is not why we love fishing, it’s just an observation.

I’d say it’s a pretty sharp observation. Did you ever face anger from the fishing community due to the lack of more conventional fishing?

Yes.

Why isn’t more television like Fishing with John? I hear we’re supposedly in the age of ‘peak TV’ or whatever, but why is there so much boring stuff out there?

The great thing about this, and a big shout out to Kenji Okabe from Telecom Japan, was they left me alone. I am fairly certain that the reason Breaking Bad was so great was because they left Vince Gilligan alone.

With most projects there are all these people meddling with what you do, to ruin it. The Gatekeepers. It is almost like there is a conspiracy to maintain mediocrity.

Going back a bit now, am I right in saying you’re from Minneapolis originally. What were you into as a child?

At first, dinosaurs and archeology. Then reptiles, particularly snakes after we moved to New Orleans. I was going to open my own snake farm. Then I was pretty sure one day, I would play center field for the Yankees.

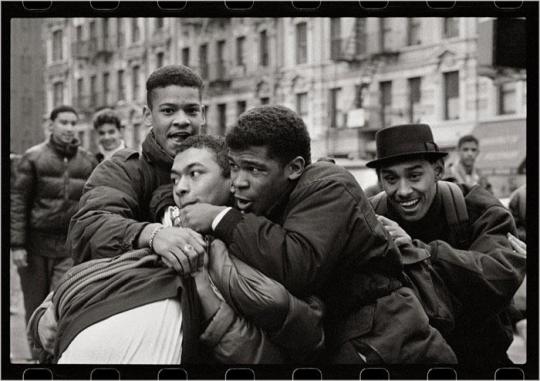

An attainable dream. You moved to New York in the late 70s, and not long after, you started The Lounge Lizards. It seems like New York at that time is glamourized a bit now, but what was it like for you? What food did you eat? Where did you go at night? What streets were good to walk down? What did it smell like?

I was trying to remember the food I ate back then and couldn’t remember. I was pretty broke most of the time. They used to serve hors d’oevres at gallery openings and cheese became a large part of my regular diet.

Almost every night, or maybe not even “almost” — more like every night — we went to the Mudd Club. More than what streets were “good” to walk down, I can tell you which streets were bad to go down. I lived on East Third St across from the Men’s Shelter, so my block smelled of rotting garbage and urine.

What are some bits that people don’t talk about from that time? What sucked about back then?

It went fairly quickly from people having more relentless fun than any period in human history to a fairly grim time, a year or two later. There was the beginning of AIDs. I had many friends who were dying or horrifyingly sick. People were getting strung out. There were many deaths. Car accidents. People fell out of windows.

Also, with the artistic promise that was there, the output is disappointing. I suppose the wildness led to a lack of discipline and the work wasn’t nearly as good as it should have been.

I might be wrong, but it seems like at that time people just did what they felt like doing… people made films, music or anything else, with no regard for budget. I suppose for example, you made a film called Men in Orbit in your apartment for $500. Where did this freedom come from?

The freedom came from a ferocious demand to have that freedom at any cost. But it is odd or sad, because the more talented of those people seem to have gone unknown and the people who are now household names are, mostly, the ones who played the game by the rules from the beginning.

Do you think people nowadays get too hung up on money? Or perhaps too hung up on success?

I think people nowadays for the most part are quite lost and afraid. So they do whatever they think they must do to have a successful career, even if it means that they are making shit — and it usually does mean they are making shit.

The Lounge Lizard’s album, Voice of Chunk is an amazing record. What sort of stuff were you listening to when you made that? And who is Bob the Bob?

The listening came from earlier in my life. Evan and I would devour everything. From Stravinsky to Monk to Little Walter to Coltrane to Tibetan music to Ellington to Dolphy to Pigmy music (you get the idea).

Later, when working on my own stuff, I stopped listening to pretty much everything. Though when I was in Morocco doing Last Temptation, I played a lot with Gnawa musicians that shifted me a bit. And around that time Evan discovered Piazzolla.

Bob the Bob is Kazu from Blonde Redhead. That is her mouth on the cover of the record. I still call her Bob.

You’re a prolific painter. Are there certain things that you notice recurring in your paintings?

I live on a small Caribbean island. There are flowers everywhere. I don’t like to think that they influence what I paint but they do. Fucking flowers.

A lot of people paint when they’re young, then stop. Why do you think that is? How come you didn’t stop?

The best paintings I have seen in the last 30 years or so are the ones taped to refrigerators. I don’t know why people stop painting or when they don’t stop, why the painting gets so stiff.

I am sure my mother, who painted herself and taught art in Liverpool where the Beatles went, but not at the same time, had something to do with me keeping a freedom in my work. To not be afraid of that childlike dream thing.

Though it has been suggested that it may be time for me to get in touch with my “inner adult.”

How do you know when a painting is finished?

I ask Nesrin. If she says it is finished, I know it isn’t.

You seem like a pretty funny guy. Do you think humour is sometimes underrated? Do people take stuff too seriously sometime?

I think humor is immensely important. I think humor can shift society’s consciousness in a better way than almost anything else. So from Shakespeare to Mark Twain to Lenny Bruce to Richard Pryor and many more – these people shifted things for the better.

Do you know who was president when Mark Twain was at his peak? Benjamin Harrison. Who the fuck was Benjamin Harrison?

What are your thoughts on the internet? It seems like it’s a big thing these days.

I get so disappointed with people because I feel like social media could be an enormously positive thing for the world. And I certainly don’t mean to exclude humor, just I have heard enough fart jokes for one lifetime…

Something that bothers me quite a bit, is a star athlete gets hurt and then the response on places like twitter is close to joy. What kind of bitterness about your own life would make you behave like that?

You’ve just recently released a new Marvin Pontiac album after 17 years. This one is called The Asylum Tapes, and was reportedly made on a four track recorder in a mental institution. Back story aside, what made you want to make an album again?

I have Advanced Lyme, so I was unable to play anything for a long time. Actually because of what was happening to me neurologically, I couldn’t even hear music for the first few years — it was more like fingernails on a blackboard.

As I slowly got better, I was able to play guitar and harmonica again, though playing saxophone would seem to be done for me in this life.

But I am very proud of this album and hope people get a chance to hear it. I made it to cheer people up.

Are people still confused about who Marvin Pontiac is?

I suppose so. He is a character I created to make this music. I suppose that is bad marketing, but fuck it.

Would the album be different if it was a John Lurie album? Do you feel like you can get away with more stuff as Marvin Pontiac? Or maybe what I mean is, is it easier to say some things as Marvin Pontiac?

Yes, absolutely. Marvin gives me a certain freedom. I doubt I would put out a record where I sing about a bear saying, “Smell my sandwich.” But I’m happy that I get a chance to do that.

The lyrics are pretty straight up and direct. Do you sit and stew on songs and ideas for long, or do you just get it out?

Often they just come straight up. Like ‘My Bear To Cross’ I pretty much just came up with it live in the studio. Some took quite a while. And there are a couple where I never found the right lyrics to finish off a song and put them aside.

Okay, last question… do you think a lot of stuff is too over-thought and over-prepared? Does thinking sometimes get in the way?

Let me think about that.